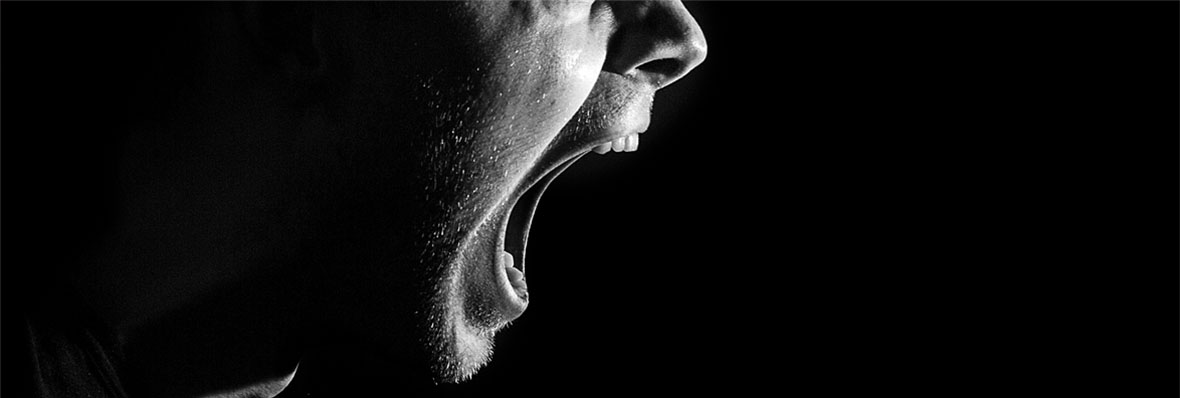

From verbal abuse to physical threats to police calls, front-line workers in the airline industry are finding themselves on the receiving end of frustrated passengers encountering flight delays and lost baggage.

“I’ve had customers poke me in the chest and say, ‘You’re not going to get me off of this flight,”’ said Cheryl Robinson, an Air Canada customer service agent at the Halifax airport.

“I’ve seen my colleagues in tears, walking away because they just can’t deal with another person yelling at them today.”

“It shakes you,” said Robinson, who’s worked at the airport for more than 24 years. “This is probably the worst I’ve ever seen.”

The frayed nerves and exploding tempers are the outcome of an ongoing struggle by airports and carriers to cope with the massive travel rebound.

Fuelled by last month’s lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, the resurgence uncorked two years of pent-up demand on a sector sagging under staffing shortages and bottlenecked airports across the globe.

Toronto’s Pearson International Airport and Air Canada have topped global lists for share of flights delayed over the past month, frequently surpassing 50 percent and fanning travellers’ ire.

“We can all understand why they’re angry and frustrated. Your flight gets cancelled and they tell you to call and you wait on hold for six hours – and I’m not exaggerating,” said Leslie Dias, director of airlines at Unifor, which represents 16,000 air transport workers, including 5,600 customer service and sales agents at Air Canada.

“To some extent, our people are broken,” she said from Calgary, where she is in negotiations with WestJet over a deal for more than 700 baggage and customer service agents.

“They’re upset, they’re often close to tears, they’re exhausted. At all airlines they’re being asked to work as many hours as they can possibly manage to work. And they feel helpless.”

Dias added that police officers are being called to airport gates daily because workers are being yelled at.

The fallout from the “sinkhole of a mess” deters new recruits and drags down retention rates, she said.

The fallout from the “sinkhole of a mess” deters new recruits and drags down retention rates, she said.

The workers in Calgary and Vancouver bargaining for their first collective agreement with WestJet start at $15.55 an hour, topping out at $23.87 an hour after seven years, she said.

On Wednesday, those workers voted 98 percent in support of a strike if they cannot reach an agreement with the airline, and could walk off the job as early as July 27, Unifor said. (See following story).

At Air Canada, the payroll is at 93 per cent of 2019 levels, while its summer flight schedule is below 80 percent of pre-pandemic volumes.

“We continue to recruit for certain jobs and have and continue to refine elements of our compensation packages to remain competitive in the current environment,” the company said in an email.

“Employees are professionals and they make every effort to manage challenging situations effectively in their respective environments. The overwhelming majority of passengers are respectful. That said, Air Canada has a zero-tolerance approach toward any kind of aggression in our business, especially towards our employees.”

Flight attendants and customs officers face their own passenger challenges as well.

“It’s like a nine-to-five job that’s now turned into a seven-day-a-week job with no fixed hours,” said Wesley Lesosky, who heads the Canadian Union for Public Employees’ airline division, which represents about 15,500 workers.

“If you have kids, if you have a family, a partner, a dog, cats … everything’s kind of up in the air.”

Frustration from long security queues, missed connecting flights, misplaced luggage and hours on tarmacs has pushed emotions to a “boiling point … resulting in increased reports of harassment and abuse – physical and verbal,” said Crystal Hill, president of CUPE 4070, which represents some 4,000 WestJet flight attendants.

“This is very scary when you’re 40,000 feet above ground.”

Border security agents also face exasperation from passengers, at least 30 percent of whom show up at land and air checkpoints without having completed their ArriveCan app, said Mark Weber, president of the Customs and Immigration Union.

“We’re seeing an uptick in verbal abuse. In many cases they’re waiting in line two, three hours to get to us. We completely get why they’re frustrated,” he said.

The increase in automated kiosks to process international arrivals at some airports has not made up for staff cuts that helped reduce customs agents at Pearson airport to the current 300 from 600 in 2017, he added.