Saturday marked three years since the World Health Organization first called the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020, and the United Nation’s health organization said it’s not yet ready to say the emergency has ended.

Not only is the death toll is nearing 7 million worldwide, but the virus is still spreading – seemingly here to stay, along with the threat of a more dangerous version sweeping the planet.

Yet most people have resumed their normal lives, thanks to a wall of immunity built from infections and vaccines.

“New variants emerging anywhere threaten us everywhere,” says virus researcher Thomas Friedrich of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Maybe that will help people to understand how connected we are.”

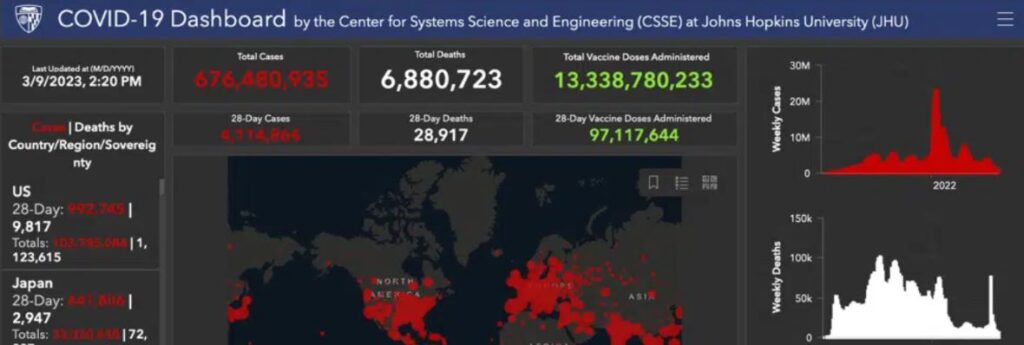

With information sources drying up, it has become harder to keep tabs on the pandemic. Johns Hopkins University on March 10 shut down its trusted tracker, which it started soon after the virus emerged in China and spread worldwide.

A look at where we stand:

The virus endures

With the pandemic still killing 900 to 1,000 people a day worldwide, the stealthy virus behind COVID-19 hasn’t lost its punch. It spreads easily from person to person, riding respiratory droplets in the air, killing some victims but leaving most to bounce back without much harm.

“Whatever the virus is doing today, it’s still working on finding another winning path,” said Dr. Eric Topol, head of Scripps Research Translational Institute in California.

We’ve become numb to the daily death toll, Topol says, but we should view it as too high. Consider that in the United States, daily hospitalizations, and deaths, while lower than at the worst peaks, have not yet dropped to the low levels reached during summer 2021 before the delta variant wave.

At any moment, the virus could change to become more transmissible, more able to sidestep the immune system or more deadly. Topol says we’re not ready for that. Trust has eroded in public health agencies, furthering an exodus of public health workers. Resistance to stay-at-home orders and vaccine mandates may be the pandemic’s legacy.

“I wish we united against the enemy – the virus – instead of against each other,” Topol says.

Fighting back

There’s another way to look at it. Humans unlocked the virus’ genetic code and rapidly developed vaccines that work remarkably well. We built mathematical models to get ready for worst-case scenarios. We continue to monitor how the virus is changing by looking for it in wastewater.

“The pandemic really catalyzed some amazing science,” says Friedrich.

The achievements add up to a new normal where COVID-19 “doesn’t need to be at the forefront of people’s minds,” says Natalie Dean, an assistant professor of biostatistics at Emory University. “That, at least, is a victory.”

Dr. Stuart Campbell Ray, an infectious disease expert at Johns Hopkins, says the current omicron variants have about 100 genetic differences from the original coronavirus strain. That means about 1% of the virus’ genome is different from its starting point. Many of those changes have made it more contagious, but the worst is likely over because of population immunity.

Matthew Binnicker, an expert in viral infections at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, says the world is in “a very different situation today than we were three years ago – where there was, in essence, zero existing immunity to the original virus.”

That extreme vulnerability forced measures aimed at “flattening the curve.” Businesses and schools closed, weddings and funerals were postponed. Masks and “social distancing” later gave way to showing proof of vaccination. Now, such precautions are rare.

“We’re not likely to go back to where we were because there’s so much of the virus that our immune systems can recognize,” Ray says. Our immunity should protect us “from the worst of what we saw before.”

Real-time data lacking

On Friday, Johns Hopkins did its final update to its free coronavirus dashboard and hot-spot map with the death count standing at more than 6.8 million worldwide. Its government sources for real-time tallies had drastically declined. In the US, only New York, Arkansas and Puerto Rico still publish case and death counts daily.

“We rely so heavily on public data and it’s just not there,” said Beth Blauer, data lead for the project.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still collects a variety of information from states, hospitals and testing labs, including cases, hospitalizations, deaths and what strains of the coronavirus are being detected. But for many counts, there’s less data available now and it’s been less timely.

Internationally, the WHO’s tracking of COVID-19 relies on individual countries reporting. Global health officials have been voicing concern that their numbers severely underestimate what’s actually happening and they do not have a true picture of the outbreak.

For more than year, CDC has been moving away from case counts and testing results, partly because of the rise in home tests that aren’t reported. The agency focuses on hospitalizations, which are still reported daily, although that may change. Death reporting continues, though it has become less reliant on daily reports and more on death certificates – which can take days or weeks to come in.

US officials say they are adjusting to the circumstances, and trying to move to a tracking system somewhat akin to how CDC monitors the flu.