Long dreamed about and in development for longer than the big league career of the man it honours, the Jackie Robinson Museum will finally open to the public in New York this weekend (Sept. 5), honouring the first black player to play in major league baseball in the 20th century.

The venue was inaugurated in late July with a gala ceremony attended by Robinson’s 100-year-old widow, Rachel, who cut the ribbon to cap a project launched in 2008.

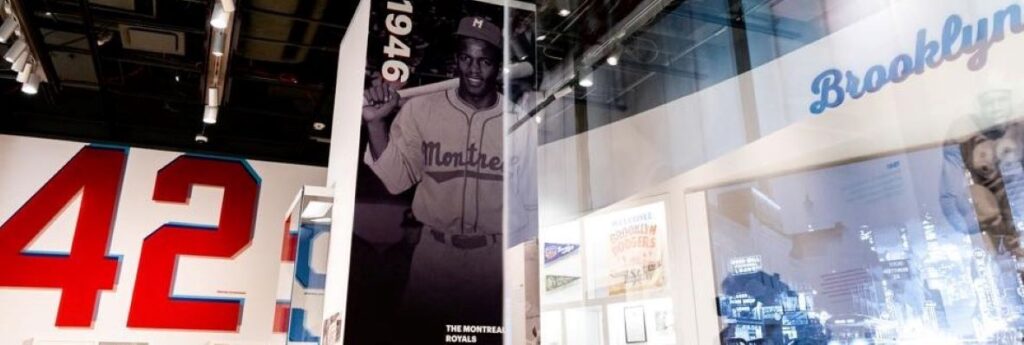

Robinson, who played for the minor league Montreal Royals in 1946, broke the colour barrier in the majors in 1947 when he took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, becoming both an unwitting, and deliberate, voice against segregation and for civil rights in the United States.

Robinson’s 72-year-old daughter, Sharon, also looked on at the ceremony from a wheelchair and 70-year-old son David spoke to the crowd of about 200 sitting on folding chairs arrayed in a closed-off section of Varick Street, a major Manhattan thoroughfare where the 1,800-sq.-m. museum is located.

“The issues in baseball, the issues that Jackie Robinson challenged in 1947, they’re still with us,” David Robinson said. “The signs of ‘white only’ have been taken down, but the complexity of equal opportunity still exists.”

Rachel Robinson announced the museum on April 15, 2008, the 61st anniversary of Jackie breaking the big league colour barrier at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

Robinson went on to become NL Rookie of the Year, the 1949 NL batting champion and MVP, a seven-time All-Star, and a World Series champion in 1955. He hit .313 with 141 homers and 200 stolen bases in 11 seasons and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

Robinson, who died in 1972, had an impact beyond baseball, galvanizing a significant slice of American public opinion and boosting the civil rights movement.

“There’s nowhere on the globe where dream is attached to our name – or our country’s name,” New York City Mayor Eric Adams said. “There’s not a German dream. There’s not a French dream. There’s not a Polish dream. Darn it, there’s an American dream. And this man and wife took that dream and forced America and baseball to say you’re not going to be a dream on a piece of paper, you’re going to be a dream in life. We are greater because of No. 42 and because he had amazing wife that understood that dream and vision.”

The museum contains 4,500 artifacts, including playing equipment and items such as Robinson’s 1946 minor league contract for US$600 a month and his 1947 rookie contract for a $5,000 salary. The museum also holds a collection of 40,000 images and 450 hours of footage.

Original projections had a 2010 opening and $25 million cost, but the Great Recession caused a delay.

Ground finally was broken on April 27, 2017, when the Jackie Robinson Foundation said it had raised $23.5 million of a planned $42 million and the museum was intended to open in 2019. The pandemic caused more delays, and the total raised has risen to $38 million, of which $2.6 million was contributed by New York City.

Tickets will cost $18 for adults and $15 for students, seniors, and children. The second floor includes an education centre, part of a plan envisioned by Rachel Robinson.

“She wanted a fixed tribute to her husband, where people could come and learn about him, but also be inspired,” said foundation president Della Britton, who headed the project. “We want to be that place, as young people now say, a safe space, where people will talk about race and not worry about the initial backlash that happens when you say something on social media.”

David Robinson said his father would have been proud.

“He was a man who used the word ‘we,’” David said. “I think today Jackie Robinson would say I accept this honour, but I accept this honour on behalf of something far beyond my individual self, far beyond my family, far beyond even my race. Jackie Robinson would say don’t think of you standing on my shoulders, I think of myself as standing on the shoulders of my mother, who was a sharecropper in Georgia, my grandmother, who was born a slave.”