As more companies start selling tickets to space, a question looms: Who gets to call themselves an astronaut? It’s already a complicated issue and about to get more so as the wealthy snap up spacecraft seats and even entire flights for themselves and their entourages.

Astronauts? Amateur astronauts? Space tourists? Space sightseers? Rocket riders? Or as the Russians have said for decades, spaceflight participants?

NASA’s new boss Bill Nelson doesn’t consider himself an astronaut even though he spent six days orbiting Earth in 1986 aboard space shuttle Columbia — as a congressman. “I reserve that term for my professional colleagues,” Nelson recently said.

Computer game developer Richard Garriott — who paid his way to the International Space Station in 2008 with the Russians — hates the space tourist label. “I am an astronaut,” he declared in an email, explaining that he trained for two years for the mission.

“If you go to space, you’re an astronaut,” said Axiom Space’s Michael Lopez-Alegria, a former NASA astronaut who will accompany three businessmen to the space station in January, flying SpaceX. His US$55 million-a-seat clients plan to conduct research up there, he stressed, and do not consider themselves space tourists.

Axiom Space has announced a second flight for next year that will be led by the company’s Peggy Whitson, a retired NASA astronaut who’s spent 665 days in space, more than any other American. Her No. 2 will be businessman-turned-race car driver John Shoffner, of Knoxville, Tenn., who’s also paying around $55 million. “I’ve asked Peggy to throw the book at me in training. Make me an astronaut,” he said.

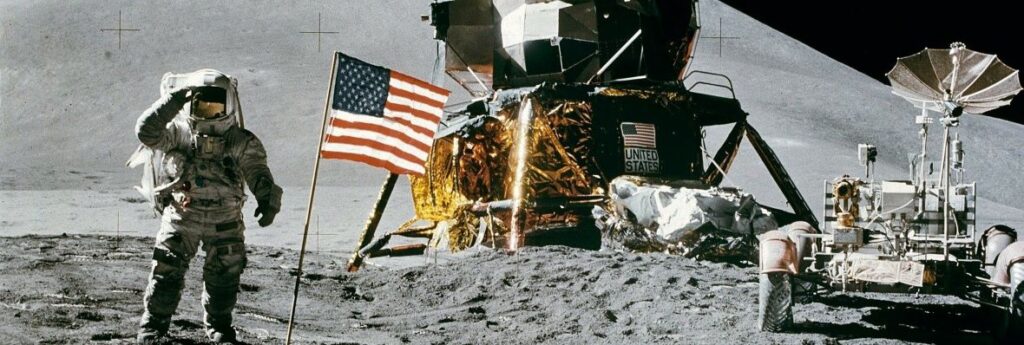

There’s something enchanting about the word: Astronaut comes from the Greek words for star and sailor. And swashbuckling images of “The Right Stuff” and NASA’s original Mercury 7 astronauts make for great marketing.

Jeff Bezos’ rocket company, Blue Origin, is already calling its future clients “astronauts.” It’s auctioning off one seat on its first spaceflight with people on board, targeted for July. NASA even has a new acronym: PAM for Private Astronaut Mission.

Retired NASA astronaut Mike Mullane didn’t consider himself an astronaut until his first space shuttle flight in 1984, six years after his selection by NASA.

“It doesn’t matter if you buy a ride or you’re assigned to a ride,” said Mullane, whose 2006 autobiography is titled “Riding Rockets.” Until you strap into a rocket and reach a certain altitude, “you’re not an astronaut.”

It remains a coveted assignment. More than 12,000 applied for NASA’s upcoming class of astronauts; a lucky dozen or so will be selected in December.

But what about passengers who are along for the ride, like the Russian actress and movie director who will fly to the space station in October? Or Japan’s moonstruck billionaire who will follow them from Kazakhstan in December with his production assistant tagging along to document everything? In each case, a professional cosmonaut will be in charge of the Soyuz capsule.

SpaceX’s high tech capsules are completely automated, as are Blue Origin’s. So, should rich riders and their guests be called astronauts even if they learn the ropes in case they need to intervene in an emergency?

Perhaps even more important, where does space begin?

The US Federal Aviation Administration limits its commercial astronaut wings to flight crews. The minimum altitude is 80 km. It’s awarded seven so far; recipients include the two pilots for Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic who made another test flight of the company’s rocket ship Saturday.

Others define space as beginning at an even 100 km above sea level.

Blue Origin’s capsules are designed to reach that threshold and provide a few minutes of weightlessness before returning to Earth. By contrast, it takes 90 minutes to circle the world. The Association of Space Explorers requires at least one orbit of Earth – in a spacecraft – for membership.

The astronaut debate has been around since the 1960s, according to Garriott. His late father, Owen Garriott, was among the first so-called scientist-astronauts hired by NASA; the test pilots in the office resented sharing the job title.

It might be necessary to retire the term altogether once hundreds if not thousands reach space, noted Fordham University history professor Asif Siddiqi, the author of several space books. “Are we going to call each and every one of them astronauts?”

Mullane, the three-time space shuttle flier, suggests using astronaut first class, second class, third class, “depending on what your involvement is, whether you pull out a wallet and write a cheque.”

While a military-style pecking order might work, former NASA historian Roger Launius warned: “This gets really complicated really quickly.”

In the end, Mullane noted, “Astronaut is not a copyrighted word. So, anybody who wants to call themselves an astronaut can call themselves an astronaut, whether they’ve been in space or not.”