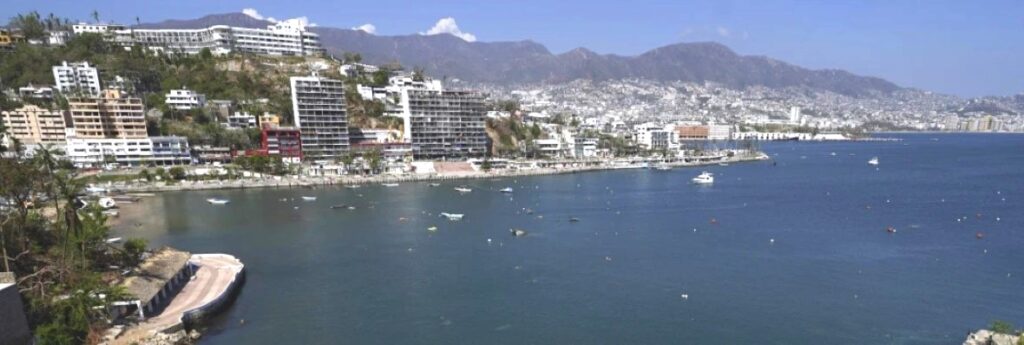

The keyboard and drums from a musical show thump just yards from a mountain of storm debris and fractured hotels left by Hurricane Otis a month ago. On the northern end of Acapulco Bay, hairdressers and masseuses sweep branches from a beach as across the Pacific resort of Acapulco, residents work with a singular purpose: to restart the tourism engine of the city of one million people as soon as possible.

“If there’s no tourism, nothing happens,” said Juan Carlos Díaz, a 59-year-old labourer waiting for food distributed by soldiers. “It’s like a little chain, it generates (money) for everyone.”

Otis, a Category 5 hurricane that smacked Acapulco on Oct. 25, damaged 80% of its hotels and 95% of its business, as well as leaving at least 48 people dead, 26 missing and impacting about 250,000 families, according to government data. Residents are striving to ensure the devastation is not a knockout blow to the once-legendary resort.

Since Acapulco’s golden era during the latter half of the 20th century – when Jackie and John F. Kennedy honeymooned there and Elvis Presley and other stars visited – the rise of other destinations like Cancun combined with organized crime to drive away international visitors.

But the city still had a devoted following of tourists who came for its beaches and nightlife. It had been hosting sporting events and major business gatherings, including an international mining conference that was in town when Otis hit. The resort boasted 20,000 hotel rooms, 377 hotels and a bevy of other vacation accommodations.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has promised that Acapulco will be ready to receive visitors this holiday season, if in reduced numbers , but not everyone believes it. Most think it will take the city a year or two to come back from Otis’ devastation.

Yair Guevara, head waiter at the Dreams hotel, one of the tall towers hollowed out by Otis’ 265 kph winds, showed up for work the day after the storm and began coordinating cleaning shifts for 20 workers. During those early days they were paid in food and basic necessities, he said.

On a recent morning, about 30 members of a collective of masseuses and hairdressers unearthed pieces of wrecked boats as they cleaned a beach on northern Acapulco Bay.

“We want the tourists to come soon,” Linda Vidal said, explaining why they were sweeping the beach.

The famous La Quebrada cliff divers who have left tourists breathless for decades have been cleaning the ocean floor of debris in the area where they end their more than 30-m. swan dives into the Pacific.

“There was a lot of debris, glass and metal,” said Eligio Álvarez, who at 50 years old still launches himself into the roiling water. He and others are rushing to set up virtual shows like they did during the pandemic to earn money until the tourists can return.

Jesús Zamora, a member of the state tourism council in Guerrero, where Acapulco is located, rebuilt part of his restaurant with fallen limbs and in four days had a section of it reopened.

Last weekend, he hosted dozens of diners, among them officials who were taking a census of the damage to the tourism sector. Zamora and others still don’t know how much aid that census will bring them or when it will come.

“We’re just hoping” that it comes, he said.

López Obrador has met multiple times with business leaders from Acapulco’s tourism sector. While they’ve kept their comments discreet, they believe the support offered so far – loans and tax extensions – are positive but insufficient.

At the Flamingos Hotel – once host to Hollywood legends John Wayne, Errol Flynn and Cary Grant – a handful of the owners’ friends recently were picking up branches and debris around the place where the most famous Tarzan, Johnny Weissmuller, spent the last years of his life.

Diana Santiago, the owner’s daughter, thinks rebuilding the pink hotel’s spartan 40 rooms will be slow because they don’t yet know where the money will come from.

“We are going to open an account (for donations) to survive these months,” Santiago said. They also plan to fall back on a survival strategy from the pandemic: selling take-out food until they can reopen the restaurant with its spectacular views. The hotel rooms will come last.

The big hotel chains also doubt they will be able to open as soon as López Obrador would like even though they swarm with workers, many who have arrived from out of state.

And even though the president has assured people that the Mexican Open tennis tournament – Acapulco’s most emblematic sporting event — will continue its uninterrupted run since 2001 in February with champions like Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, the organizers have yet to confirm that.

The Princess hotel, the enormous glass and balconied pyramid where the tennis players stay, has not said when it will reopen. Otis left it in skeletal form.

The government has declared an end to the emergency in Acapulco, but many in the city still lack the basic necessities and mountains of garbage and debris continue to clog streets.

Gregorio García, a cab driver who was back to work after the storm as soon as he could patch a tire and find gasoline, conceded there are residents who complain that the tourism sector is prioritized in recovery efforts. He still doesn’t have electricity or water at home, but he doesn’t agree with the complaints.

“If there aren’t tourists, there’s nothing,” he said.