Boeing, an icon in American manufacturing, suffered its first annual financial loss in more than two decades while the cost of fixing its marquee aircraft after two deadly crashes doubled to more than US $18 billion. Boeing reported a loss of $1 billion in the fourth quarter as revenue plunged 37% due to the grounding of the Max. The company suspended deliveries of the plane last spring and hadn’t expected the stoppage to last this long.

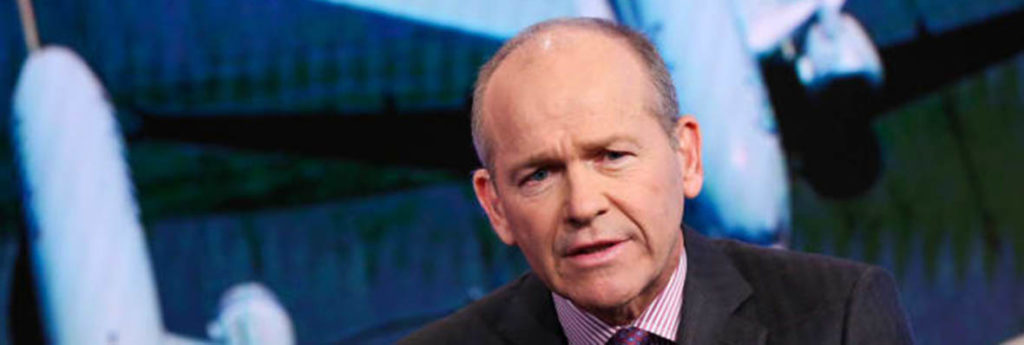

New CEO David Calhoun on Wednesday stood by his estimate that regulators will certify changes Boeing is making to the 737 Max by mid-year.

Calhoun criticized the company’s prior leadership for not immediately disclosing a trove of damning internal communications that raised safety questions about the Max. He promised to be more transparent.

“I have to restore trust, confidence and faith in the Boeing Co.,” he told Wall Street analysts.

The company lost US $636 million for all 2019, compared with a profit of nearly $10.5 billion in 2018. It was the first annual loss since 1997, when Boeing was roiled by parts shortages, production delays, and expenses from merging with McDonnell Douglas.

Problems aren’t limited to the Max.

Slowing demand for larger jets led the company to announce it will reduce production of the 787 Dreamliner, and a decision on whether to build a new mid-size plane to compete with a model from rival Airbus has been delayed.

Revenue in the company’s defence and space business fell 13% and it took a US $410 million charge in case NASA requires another unmanned flight of Boeing’s Starliner – the spacecraft that failed to reach the International Space Station during a test flight in December.

The company’s focus, however, is on fixing the Max.

The plane was grounded worldwide last March, after two crashes within five months killed 346 people in Indonesia and Ethiopia. The crisis torpedoed sales and deliveries of new jetliners, leaving Boeing far behind Airbus. It caused a shutdown in Max production, layoffs at suppliers, and led to the firing of CEO Dennis Muilenburg.

US airlines that own Maxes – Southwest, American and United – don’t expect it back until after the peak of the summer travel season. It is anyone’s guess about how willing passengers will be to fly on the plane.

A sound airplane

The head of the Federal Aviation Administration, Stephen Dickson, told US airline officials late last week that he was content with Boeing’s progress toward getting the Max back in the year, raising the possibility that the plane could fly sooner than Boeing has estimated.

Calhoun said Wednesday he appreciated Dickson’s comments, but they wouldn’t cause him to change Boeing’s projection of regulatory approval by midyear because Dickson could change his tune in a month.

Calhoun insisted the Max “is a sound airplane” that will be safer than ever after extensive tests and scrutiny by the FAA. He said passengers will fly on it once they see pilots get on board.

“Airplanes unfortunately have gone down before,” he told reporters. “People take a breath and wonder whether they’ll ever fly one again … and then slowly and steadily, they do.”

Boeing won’t change the name of the plane either, as Donald Trump and others have suggested. “I’m not going to market my way out of this,” Calhoun told CNBC.

Frankly it’s unlikely that he could do that. There is no evidence that a name change would work. In today’s climate of leaks and whistleblowers, such a tactic would almost certainly be quickly exposed, backfiring on Boeing and leaving the company with an even greater public relations nightmare.

Boeing has been embarrassed in recent weeks by the disclosure of years-old internal messages in which test pilots and other key employees raised safety concerns about the Max – even saying they wouldn’t put their families on it – while the plane was in development and testing.

Calhoun criticized company leaders who didn’t disclose the messages right away. He said if the right people in leadership had seen the employee concerns about the Max, they might have pushed for training in flight simulators before pilots could fly the Max. Boeing recently reversed its longstanding and determined opposition to simulator training, which will add time and expense before airlines can use the plane.

Calhoun, a former General Electric and Nielsen executive who had been on Boeing’s board since 2009, became CEO this month.

For the fourth quarter, Boeing booked another US $9.2 billion in estimated current and future extra costs for production delays, deliveries, and compensation for airlines that have cancelled tens of thousands of Max flights. That raised Boeing’s estimate of the total financial hit from the crisis to US $18.6 billion.

Cowen analyst Cai von Rumohr said the charge for airline compensation was about US $4 billion less than most investors had feared.

Revenue tumbled to US $17.9 billion, far below Wall Street’s forecast of US $21.7 billion, according to a FactSet survey of analysts.

For all the troubling news from the company, investors were happy that the damage wasn’t worse. Shares rose rose 2.2% to US $323.52 in afternoon trading.