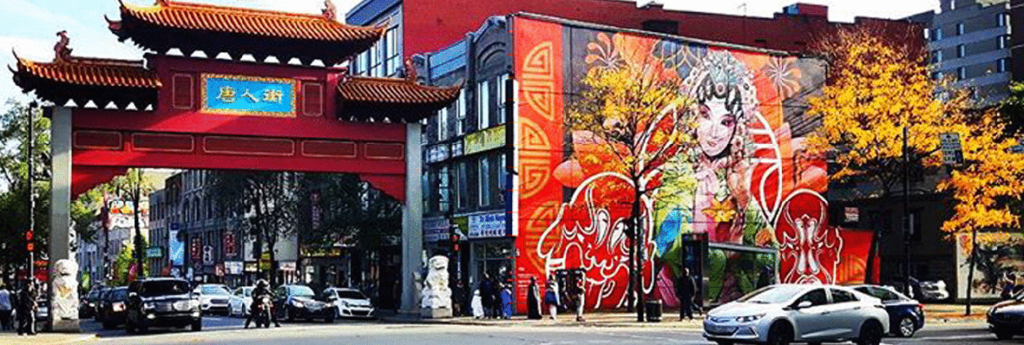

Hotels and luxury condos have sprung up around the ornate red and gold gate that marks the south entrance to Montreal’s Chinatown, towering above the busy dumpling restaurants and mom-and-pop stores.

The threats of development and gentrification have prompted a recent wave of concern from politicians, but advocates say the action may not be coming fast enough to preserve a neighbourhood that has been historically ignored and further undermined by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jonathan Cha, a Montreal landscape architect and Chinatown expert, says concern over the downtown neighbourhood’s future hit a new high recently when a developer purchased buildings on one of its most historic blocks – including the Wing’s building, named for a noodle factory that has long operated there. A light-rail system is also planned to pass by Chinatown, further hemming in the neighbourhood.

He said Montreal has no specific rules to control development in Chinatown, leading to the proliferation of luxury condos, gentrification and rising rents that threaten the vibrant community life. “The main danger is that Chinatown, especially de la Gauchetiere Street, will become just a tourist restaurant area with nice lanterns and a few colours and decorations … but Chinatown is not just that,” Cha said in a phone interview.

“We want to make sure that we preserve the buildings where people meet and gather, where they still have a Buddhist temple, and the family association, and community equipment, cultural venues.”

In recent months and years, Cha said he’s seen momentum growing among concerned residents and businesses, and politicians are beginning to take notice.

The City of Montreal has promised to deliver an action plan for Chinatown in the coming weeks, following consultations that began two years ago. Mayor Valerie Plante and the province also announced last month the creation of a committee whose goal is to protect the neighbourhood’s heritage.

Last week, Plante was among the politicians present at a forum hosted by the Chamber of Commerce of Metropolitan Montreal that brought together all three levels of government and community members.

Those in attendance agreed the COVID-19 pandemic hit Chinatown particularly hard. While businesses have suffered everywhere, the area had to contend with not only a sharp decline in tourism and office worker traffic, but also a wave of anti-Asian racism that cast a “baseless shadow”’ over the community, said Chantal Rouleau, the provincial legislature member responsible for Montreal.

The solutions proposed included working with developers to make sure they respect the history of the neighbourhood, granting heritage status to some buildings, promoting local tourism to the area and funding for programming and businesses.

But while the attention given to the area is welcome, activists say there are still too many words and not enough action.

Cha and other members of the Chinatown working group have long been calling for the provincial and municipal governments to grant the neighbourhood and some of its buildings heritage designation – something that has not yet been done. They also say rules need to be set to ensure new development respects the area’s history.

“The zoning tools just don’t make sense with the type of built environment,” he said. “In some areas, you can build a 20-storey building where you have buildings of three storeys dating from the mid-19th century.”

While he’s hopeful for change, Cha said the problems facing Chinatown have come about after decades of neglect – or worse – from city officials.

Much of Chinatown was already torn down in the 1960s and 1970s to make way for big projects including a large government office complex.

Montreal’s Chinatown is far from the only one in this situation, according to Karen Cho, a filmmaker and member of the Chinatown Working Group.

Across North America, Chinese immigrants formed such neighbourhoods because of racist laws and attitudes that barred them from living and doing business elsewhere, she said. While they were once seen as slums and denied basic services such as garbage pickup, they’ve now become prime targets for developers because they contain older buildings close to downtown cores.

Cho says she’s frustrated that authorities have consistently resisted suggestions to protect Chinatown, such as a heritage designation and moratorium on development while planning tools are developed.

“Chinatown in a way is in a real triage situation, like when someone’s limb has been cut off and they’re bleeding out,” she said. “So the heritage protection is that tourniquet that stops the bleeding, so we can have time to address other issues.”

She says to lose Chinatown would be to lose a piece of Montreal and Canadian history, which includes not just Asian Canadians but many other immigrant groups who settled there over the years

However, she said the neighbourhood is not just historical. It’s also the kind of diverse, walkable, human-scale place most modern planners strive for.

“It can easily be a blueprint for the kind of neighbourhood we want to build for the future of Montreal: livable, walkable accessible, affordable,” she said.