Ukrainian leaders say one of the best ways for Canadians to support the embattled country’s economy is to pack their bags and come see it for themselves. “If you’re brave, welcome to Lviv,” says mayor Andriy Sadovyi.

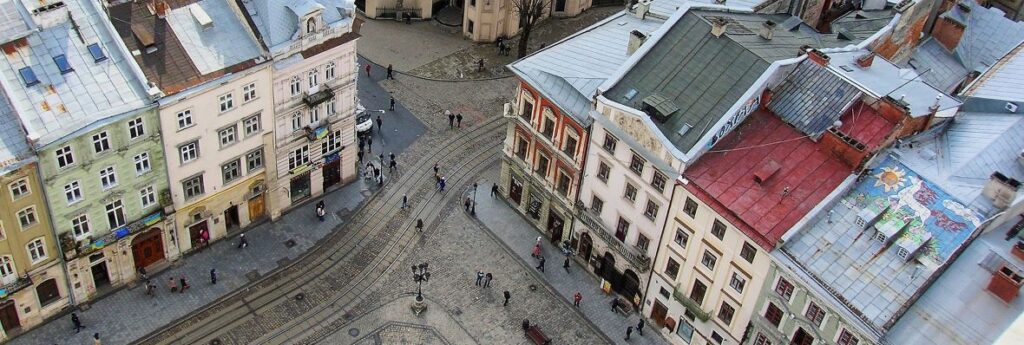

The mayor spoke from his office in the city’s town hall, in the heart of the cobblestoned streets of Old Town. Located about 70 km from the Polish border in western Ukraine, the area is relatively safe compared to the rest of the country.

The streets sparkle with twinkly lights around the doorways of independent shops and vibrant restaurants, as small crowds of people bustle past ornate neo-Gothic and renaissance buildings.

But the charming sights are interrupted by jarring signs of war around every corner. Air raid sirens are an almost daily occurrence, though many people in the city do not heed them anymore. A curfew has been imposed under martial law, putting a slight damper on the nightlife.

Monuments are wrapped in burlap, boarded up with plywood and guarded by anti-tank traps to protect them from potential enemy shelling. Sandbags are stacked along basement windows so they can be used as makeshift bomb shelters. Military checkpoints block entrances to the city.

On a sunny day in February on a major promenade near the Lviv Opera House, a small boy plays a carnival game. He shoots a photograph of Russian President Vladimir Putin with a realistic-looking toy rifle.

Despite the mayor’s welcome, the municipality cannot actively encourage people to enter Ukraine. There is no way to guarantee they will not be targeted by a Russian missile attack, Khrystyna Lebed, who heads the tourism centre, said through a translator.

The Canadian government issued a travel advisory strongly urging Canadians to avoid all travel to the country because of the risks posed by the Russian invasion. Travel insurance is expensive and difficult to get.

“It may sound strange, but we do invite people not to be afraid to visit,” Ukrainian Railways’ passenger company CEO Oleksandr Pertsovskyi said in an interview from Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital city. “Because the economy is struggling and of course incoming tourism could become one of the sources.”

Pertsovskyi said visitors need to decide for themselves how comfortable they are with the risk. But he underlined that making the journey to Ukraine could be one of the strongest ways for Canadians to support the war effort.

“We believe as soon as the situation stabilizes to a certain extent, people, and Canadians in particular, will start visiting at least the west of Ukraine,” he said.

The rail company has even created a scenic train route for tourists from Moldova to Kyiv called the “Victory Train,” and decorated each train car to represent an occupied territory of the country.

In Lviv, the tourism office has made an effort to point out the comparatively low frequency of rocket attacks in the region compared to other parts of the country, and how far Lviv is from the front lines of the war: about the distance between Calgary and Vancouver.

It has also started advertising which hotels in the city have their own bomb shelters.

Mayor Sadovyi says his people have come up with innovative ways to adapt to the difficult circumstances of the war. They have carried on with “resilience, bravery and huge love for motherland.”

When Russian bombs wiped out power infrastructure, restaurants and hotels bought generators to keep their businesses running. They can be seen lining the sidewalks outside of nearly every business in the city’s core.

Several new restaurants have opened in the city’s cellars. Some of the new eateries are run by restaurateurs from occupied territories who have started their businesses anew in Lviv.

“We every day come up with different new idea about our resilience,” said Sadovyi, who has been the city’s mayor for 17 years.

He said he has consulted with other tourism centres in countries facing conflict, including in Croatia and Israel, about how to balance the economic desire for tourists with the safety considerations of war.

Ultimately, he said, those places are learning from Lviv, too.

“I think today in Ukraine we have very unique case, and our example is very interesting for a lot of mayors in different countries.” All who arrive to Lviv are “my guests,” said Sadovyi.

A year after the war began, most of the people who come to the city are people from elsewhere in Ukraine who are looking for a short getaway, said Lebed, from the tourist centre.

Ukrainians fleeing their homes near the front lines, international journalists, aid workers and political delegations from other countries have also been paying into the city’s economy with their stay.

But week by week, the number of international tourists is inching up. Their support, Lebed said, is “priceless.”