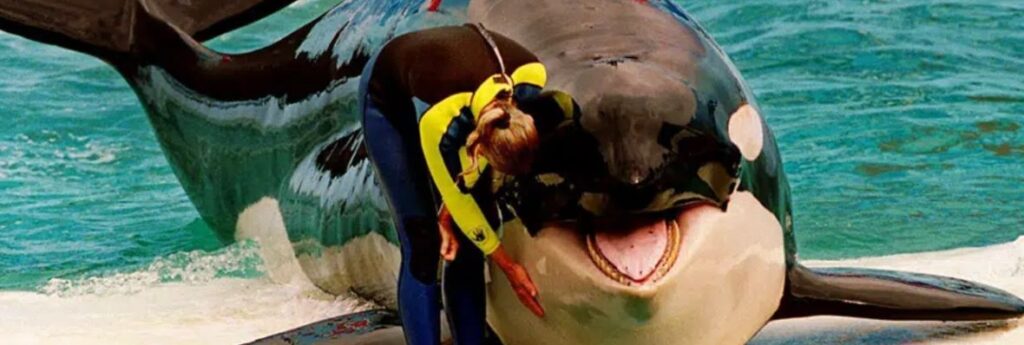

If you’ve been to Miami Seaquarium during the past 52 years, you’ve probably met Lolita, who has been performing for guests since the ‘70s. Now the famed orca may be returned to her home waters in the Pacific Northwest, where a nearly century-old, endangered killer whale believed to be her mother still swims.

An unlikely coalition involving the theme park’s owner, an animal rights group and an NFL owner-philanthropist announced the agreement during a news conference late last week.

“I’m excited to be a part of Lolita’s journey to freedom,” Indianapolis Colts owner Jim Irsay said. “I know Lolita wants to get to free waters.”

Lolita, also known as Tokitae, was about four years old when she was captured in Puget Sound in summer 1970, during a time of deadly orca roundups. She spent decades performing for paying crowds before falling ill.

Last year the Miami Seaquarium announced it would no longer stage shows with her, under an agreement with federal regulators. Lolita – now 57 years old and 2,267 kg. – currently lives in a tank that measures 24 by 11 m. and six metre deep.

The orca believed to be her mother, called Ocean Sun, continues to swim free with other members of their clan – known as L pod – and is estimated to be more than 90 years old. That has given advocates of her release optimism that Tokitae could still maybe have a long life in the wild.

“It’s a step toward restoring our natural environment, fixing what we’ve messed up with exploitation and development,” said Howard Garrett, president of the board of the advocacy group Orca Network, based on Washington state’s Whidbey Island. “I think she’ll be excited and relieved to be home – it’s her old neighbourhood.”

The agreement among Irsay; Eduardo Albor, who heads The Dolphin Company, which owns the Seaquarium; and the Florida non-profit Friends of Toki, co-founded by environmentalist Pritam Singh; still faces hurdles to gaining government approval.

The time frame for moving the animal could be 18 to 24 months away, the group said, and the cost could reach US$20 million.

The plan is to transport Lolita by plane to an ocean sanctuary in the waters between Washington and British Columbia, where she will initially swim inside a large net while trainers and veterinarians teach her how to catch fish.

She will also have to build up her muscles, as orcas typically swim about 160 km per day, said Raynell Morris, an elder of the Lummi Indian Tribe in Washington who also serves on the board of Friends of Toki.

“She was four when she was taken, so she was learning to hunt. She knows her family song,” Morris said. “She’ll remember, but it will take time.”

The orca would be under 24-hour care until she acclimates to her new surroundings.

Caretakers at the Seaquarium are already preparing her for the journey, officials said.

The Dolphin Company took ownership of the Seaquarium in 2021. It operates some 27 other parks and habitats in Mexico, Argentina, the Caribbean, and Italy.

The legacy of the whale roundups of the 1960s and ’70s continues to haunt a distinct group of endangered, salmon-eating orcas that are known as the southern resident killer whales and spend much of their time in the waters between Washington and BC.

At least 13 orcas died in the roundups and 45 were delivered to theme parks around the world, reducing the Puget Sound resident population by about 40% and helping cause problems with inbreeding that remain a problem today.

Today only 73 remain in the southern resident population, which comprises three familial groups called pods, according to the Center for Whale Research on Washington state’s San Juan Island. That’s just two more animals than in 1971.

Animal rights advocates including People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals have long fought for Tokitae to spend her final years back home in a controlled setting.

Activists often protest along the road that runs by the Seaquarium, which they’ve referred to as an “abusement park.” PETA says it doesn’t want Lolita to suffer the same fate as her partner Hugo, who died in 1980 from a brain aneurysm after ramming his head repeatedly into the tank’s walls.