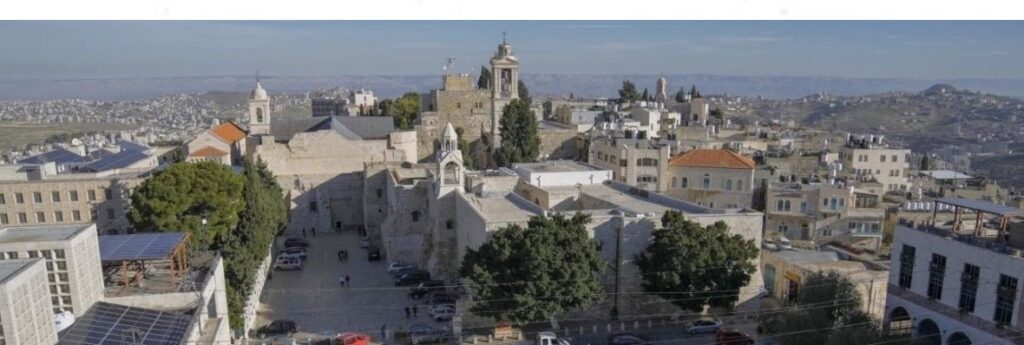

Bethlehem is gearing up for a subdued Christmas, without the festive lights and customary Christmas tree towering over Manger Square, after officials in Jesus’ traditional birthplace decided to forgo celebrations due to the Israel-Hamas war. The cancellation of Christmas festivities, which typically draw thousands of visitors, is a severe blow to the town’s tourism-dependent economy.

City mayor Hana Haniyeh says joyous revelry is untenable at a time of immense suffering of Palestinians in Gaza. But, not surprisingly, tourists are also staying away.

Since Oct. 7, access to Bethlehem and other Palestinian towns in the Israeli-occupied West Bank has been difficult, with long lines of motorists waiting to pass military checkpoints. The restrictions have also prevented many Palestinians from exiting the territory to work in Israel.

And with most major airlines cancelling flights to Israel, over 70 hotels in Bethlehem have been forced to close, leaving some 6,000 employees in the tourism sector unemployed, according to Sami Thaljieh, manager of the Sancta Maria Hotel.

The yearly Christmas celebrations in Bethlehem – shared among Armenian, Catholic, and Orthodox denominations – are major boons for the city, where tourism accounts for 70% of its yearly income. But the streets are empty this season.

“I spend my days drinking tea and coffee, waiting for customers who never come. Today, there is no tourism,” said Ahmed Danna, a Bethlehem shop owner.

Haniyeh said that while Christmas festivities have been cancelled, religious ceremonies will take place, including a traditional gathering of church leaders and a Midnight Mass.

“Bethlehem is an essential part of the Palestinian community,” the mayor said. “So, at Midnight Mass this year, we will pray for peace…”

The enthusiasm of Bethlehem’s Christmas festivities have long been a barometer of Israeli-Palestinian relations.

Celebrations were grim in 2000 at the start of the second intifada, or uprising, when Israeli forces locked down parts of the West Bank in response to Palestinians carrying out scores of suicide bombings and other attacks that killed Israeli civilians.

Times were also tense during an earlier Palestinian uprising, which lasted from 1987-1993, when annual festivities in Manger Square were overseen by Israeli army snipers on the rooftops.

The sober mood this year isn’t confined to Bethlehem.

Across the region, Christmas festivities have been put on hold. There are 182,000 Christians in Israel, 50,000 in the West Bank and Jerusalem and 1,300 in Gaza, according to the US State Department. The vast majority are Palestinians.

In Jerusalem, the normally bustling passageways of the Old City’s Christian Quarter have fallen quiet since the war began. Shops are boarded up, with their owners saying they are too frightened to open – and even if they did, they say they wouldn’t have much business.

The heads of major churches in Jerusalem announced in November that holiday celebrations would be cancelled. “We call upon our congregations to stand strong with those facing such afflictions by this year foregoing any unnecessarily festive activities,” they wrote.

At the altar of Bethlehem’s Evangelical Lutheran church, a revised nativity scene is on display. A figure of baby Jesus wrapped in a Palestinian keffiyeh is perched atop a pile of rubble. The doll lies underneath an olive tree – for Palestinians, a symbol of steadfastness.

“While the world is celebrating, our families are displaced and their homes are destroyed,” said the church’s Pastor, Munther Isaac. “This is Christmas to us in Palestine.”