On March 24, 80 years ago, in one of the most ingenious and audacious acts of defiance of World War II, 76 prisoners of war tunneled out of a German POW camp into a snowy forest. For most of the escapees, it ended tragically. Three made it to safety, but the others were recaptured and 50 of them were executed.

Nevertheless, the event became known as the “Great Escape,” credited with embarrassing the Germans and celebrated in a 1963 film starring Steve McQueen that took liberties with the facts but became the stuff of legend.

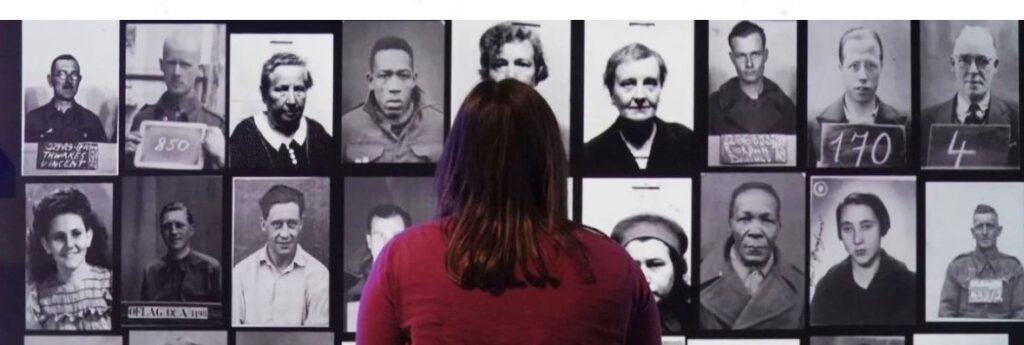

Few managed to make such bold dashes to freedom during the war, but an exhibit has opened the UK National Archives in London uses the 80th anniversary of the breakout as an entry point to explore escapes of all types – some physical, others creative – to ease the tedium and torment of captivity among prisoners of war and civilians held in internment camps in Europe and Asia.

“They had to endure those facilities for as long as it took,” said Roger Kershaw, one of the curators of “Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives.” “They had no idea when the war was going to end. So, a lot of them would immerse themselves into writing.”

The exhibit, which runs until July 21, came about after the archives, which contain 11 million records dating back 1,000 years, acquired 200,000 records of British Commonwealth and allied prisoners of war and civilians who were held captive during the war.

One of the exhibits features the British writer P.G. Wodehouse, who was living in France in 1940 when he was arrested as an “enemy alien,” taken to a camp in Poland and held for nearly a year. During his incarceration, he persuaded the commandant to get him a typewriter and he wrote two novels, including “Money in the Bank.”

A copy of the book is on display, along with an internee card that misspelled his name and a Saturday Evening Post article about his life as an internee.

The exhibit also includes artifacts from German nationals arrested in Britain as enemy aliens and sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man

Jewish refugee Heino Alexander, who was born in Germany, documented in a diary the hellish 58-day journey from Liverpool to Sydney with 2,500 others aboard a passenger ship called the HMT Dunera. He described cramped conditions living below deck behind barbed wire, where he wrote about being homesick and missing his “dear love” wife. He said they had no washing facilities, soap, or toothbrushes.

“For the first days we could not even get onto the upper deck to gasp some fresh air,” he wrote.

“People were looted, luggage was thrown overboard,” Kershaw said. “Jewish refugees were actually housed on the boat alongside pro-Nazis. So, there’s lots of friction as well. And the boat narrowly avoided being torpedoed. It was a horrendous journey.”

In Asia, after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese in February 1942, some 50,000 troops and civilians, mostly British and Australian, were imprisoned at Changi camp.

Ronald Searle, a British soldier, was sent to Changi camp as a POW before being shipped off to the Thai jungle to work on building the Thai-Burma railway where cholera outbreaks reduced the population of some camps by half within weeks. Searle survived several illnesses and found peace by secretly making 300 drawings that documented life as a prisoner and the cruelty of his captors.

While actual escape was impossible in many of these situations, Military Intelligence 9 (MI9), a secretive British agency, was created in 1939 to train troops what to do if cut off from their comrades and how to escape if captured.

MI9 – said to have inspired Q, the gadget master in the James Bond movies – created uniforms with secret pockets to hide compasses, playing cards with hidden maps, and a flight boot with a knife concealed inside that could be used to cut the top off so it looked like an ordinary shoe.

A glass case displaying some of the items or diagrams and the MI9 “bible” on evasion and escape techniques also includes a seemingly innocuous photo of a Royal Marine pilot, Guy Griffiths, who had been shot down and imprisoned at Stalag Luft III, the prisoner of war camp where the Great Escape took place.

Griffiths, who was also focused on intelligence, created meticulous sketches of phony British aircraft, such as the Westland Wildcat, that he would leave in places for his captors to find, as a way of misleading them.

The camp, however, was best known for the events that unfolded on the night of March 24, 1944.

The camp had been built on sandy soil and barracks were elevated off the ground to prevent the possibility of building tunnels. Many of the officers held there, like Bertram “Jimmy” James, were prolific escape artists and they got to work on a bold plot.

Over the course of about a year, the men secretly dug three tunnels named Tom, Dick, and Harry. The Germans discovered the first tunnel but the other two remained.

The plan was to get 200 men out through tunnel Harry, but on the night of the escape, the first man who emerged realized the tunnel did not extend as far beyond the wire as they had anticipated. Only 76 made it out before a guard noticed footprints in the snow.

In a recording in the exhibit, James discussed the construction of the tunnel – including exchanges along the way named Piccadilly Circus and Leicester Square, after stops on the London Underground – and the moment he emerged as the 39th man to get out.

“On reaching the exit, I stood up and saw the stars above me,” James said. “It was a very euphoric moment. I was free at last.”

It was a fleeting feeling. James was caught within a day, though he was one of the 23 lucky men whose lives were spared. Three men – two Norwegian pilots and a Dutch pilot – were the only successful escapees.

Adolf Hitler was so incensed by the escape that he had ordered executions of the 73 recaptured men, and the Nazis eventually settled on killing 50 – all in violation of the Geneva Conventions on treatment of war prisoners.

After the war, the murders of the allied airmen were part of the Nuremberg trials and several Gestapo officers were sentenced to death.